Fun with switch case, Part I

The switch-case construction has some interesting quirks. Continue reading →

The switch-case construction, or switch statement, provides your code with a decision tree that both easy to read and to debug. This construction is a bit daunting for the beginner, but becomes more familiar as you use it. It’s not without its quirks.

As a review, the switch statement is followed by an expression.

switch(a)

The expression is often a single variable, a above, though it can be any valid C language expression. The result of this expression is compared with a block of case statements:

case const:

Each case keyword is followed by a constant, which is compared with the switch statement’s expression. When a match is made, the statements following case are executed. Otherwise, the statements are skipped.

An optional default statement handles any condition not met with the case statements.

The switch-case construction affects flow control like if-else. It’s elegant in its construction, but not as versatile as an if statement, which can be coupled with else-if statements to hone the results.

The switch-case construction was around long before the C language was invented. Its popularity is evident in that it appears in a variety of programming languages.

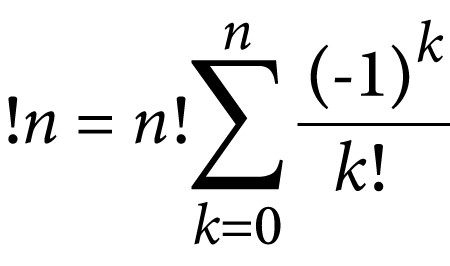

One peculiarity with switch-case is that you cannot use a constant symbol in a case statement. You can use a defined constant, which is set by the precompiler. But a constant symbol isn’t really a constant in C, and some compilers don’t allow its use in switch-case.

As a reminder, you use the #define preprocessor directive to create a defined constant:

#define THREE 3

A symbolic constant is created like a variable:

const int three = 3;

It’s this second example that makes compilers choke.

2024_02_24-Lesson.c

#includeint main() { const int two = 2; int a; printf("1, 2, 3: "); scanf("%d",&a); switch(a) { case 1: puts("One!"); break; case two: puts("Two!"); break; case 3: puts("Three!"); break; default: puts("You bad!"); } return 0; }

In this code, constant two is set to the value 2. It appears as the second case statement. You would assume that if two were truly a constant, it should work.

When compiled under clang, I see no warnings or errors. The code runs as expected, with two representing the value 2. But when compiled under gcc, the following is output:

2024_02_24-Lesson.c: In function ‘main’:

2024_02_2024_02_24-Lesson.c: In function ‘main’:

2024_02_24-Lesson.c:16:17: error: case label does not& reduce to an integer constant

16 | case two:

| ^~~~

2024_02_24-Lesson.c:5:19: warning: variable ‘two’ set but not used [-Wunused-but-set-variable]

5 | const int two = 2;

|

The gcc compiler provides a better reaction than clang, which is more forgiving (at least in my configuration).

My advice is not to use a symbolic constant in a case statement. In fact, technically speaking, a constant in C isn’t a constant at all: It’s merely a symbol (variable) that the compiler accepts as “holy” or unalterable by the code. (Devious ways exist to mangle a symbolic constant, which I’m not going into here.)

While this switch-case quirk is more of a C language quirk, it’s still worth noting. For next week’s Lesson I cover another interesting aspect of the switch-case construction, one that surprised me.

What's Your Reaction?

![Canva Tutorial For Beginners | How to Use Canva Like PRO [FREE] | Canva Full Course](https://img.youtube.com/vi/yWJp7gQqCQ8/maxresdefault.jpg)